An update on my health

FINALLY. A small glimmer of hope in the despair that has been my health situation this past year.

After surviving a cardiac arrest in 2019, my heart issues came back with vengeance late 2020 in the middle of the pandemic. I’ve spent weeks at a time at hospital, including over Christmas and NYE, getting discharged only to come back in an ambulance a few days later, enduring multiple 5-hour long awake surgeries and getting injected with toxic drugs to the point where both my arms were badly inflamed with blod clots.

This is a post on my strange case and how we arrived on what finally looks like a viable treatment.

Every single day the past year, I have lived in terror, never knowing which one of my sometimes thousands of irregular heart beats will unleash an electrical storm (yes, that is the medical term). Constantly being aware of my surroundings as to avoid falling badly in case I would pass out at the worst possible moment. I’ve been picked up by ambulance dozens of times and at its worst I had 10 cardiac arrests in a single day, going in & out of consciousness at the ICU, not knowing if I was still alive or already dead.

What saved me time and time again the past year was my ICD – an implanted defibrillator I got after my first cardiac arrest. Mine is programmed to wait & allow me to faint before it jolts my chest with 800 Volts and reboots the heart. A few times, I’ve been still awake though and while I’ve never been kicked by a horse, now I have something to compare with.

During this time, somewhere around 30-40(?) doctors in different countries have been involved in my case, unable to find anything conclusive despite multiple electrophysiological examinations, MRIs, echographies, coronary angiography, scintigraphy, genetic tests and hundreds of blood samples.

Early on, doctors noted I had unusually low phosphate levels in my blood whenever my heart was acting up so first line of treatment was to keep phosphate levels up with supplements. Genetic testing revealed i had something called FHH: Familial Hypocalciuric Hypercalcemia. Word for word this means that I have too much calcium in my blood because I pee too little of it. Since calcium and phosphate are regulated together, the theory was that this caused my dips in phosphate levels. Unfortunately this was just a small piece of the puzzle. Treating the phosphate levels didn’t work and even though I was supplementing, they sometimes dropped fast in a way doctors had only seen in patients with kidney transplants or anorexia (refeeding syndrome), and even in these cases there were no association with cardiac issues.

Next up, the proposed solution was ablation – a procedure where you enter a catheter into a vain from the groin, leading to the inside of the heart to burn or freeze tissue suspected of causing premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). In my case, these sometimes lead to ventricular fibrillation – an electrical feedback loop where the ventricles flutter at 400+ beats per minute, losing their blood pumping function and leading to cardiac arrest.

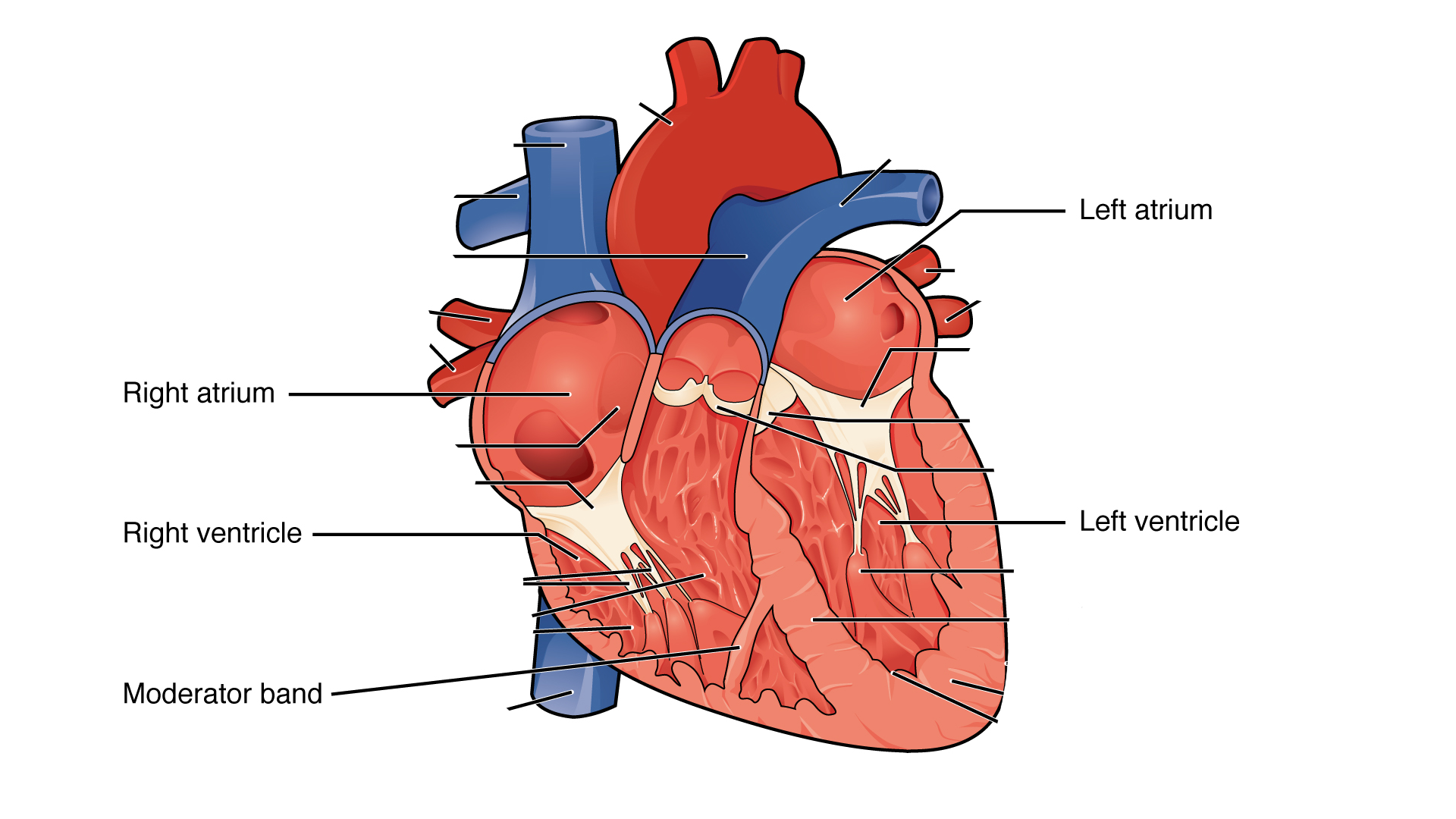

The problem in my case, is that the suspect tissue is in a really tricky place - the moderator band. This is a string of muscle going across the inside of the right ventricle. Since ablation procedures are usually done while you are awake, this also means the heart is beating and constantly moving around. It’s like trying to grill a piece of meat with a hot stick from the inside of a tumbler. The experience is all very strange, laying in a lab for hours while doctors painstakingly probe your heart with electricity, trying to trigger the fatal arrhythmias before frying it from the inside.

“Last time, we managed to fry the tissue medium-rare. This time, we’ll make it well-done”

Sadly, the attempts weren’t enough to stop my arrhythmias. As I got home, my symptoms got progressively worse over time. My measuring stick was ”The staircase of terror” – an uphill walkway from a nearby subway station. On a good day, I could walk it up slowly without breaks. On a bad day, I was getting passed by pensioners in their 80s as I had to repeatedly stop and wait for my heart to calm down between palpitations.

Three months after my third ablation procedure, I had another fainting episode and was rushed into hospital yet again. At this point, the electrophysiologists saw no point in trying the procedure again, thus there were two options:

1: An epicardial ablation on the outside of the heart instead of through the inside. This is a riskier procedure since you have to penetrate the heart sack holding the heart in its place, risking stabbing the heart itself & causing internal bleeding. In all of Stockholm, this is only done about once a year as a last resort on very ill patients.

2: Anti-arrhythmic drugs, which unfortunately are double-edged swords. They act by blocking different ion channels in heart cells, which makes them produce electric potential more slowly and thus supposed to calm the heart. But it’s a dangerous game as inhibiting one ion channel can have unpredictable consequences on the combined electrical potential. Sometimes, the drugs help, other times, they make things a lot worse as I was about to experience.

Model of electric potential inside ventricular heart cells. http://www.vhlab.umn.edu/atlas/conduction-system-tutorial/control-of-ones-heart-rate.shtml

The first try was with Flecainide, a drug which acts by blocking sodium ion (Na+) channels. In my case, this was a complete disaster.

For two days, I was unable to do much more than drinking protein shakes from a straw in bed while my ECG-monitor beeped with warnings. Even the tiniest exertion such as taking a sip triggered floods of PVCs and eventually a near-fainting episode caused by a Torsade de Pointes. I had actually already have a previous run with this drug during last fall, then resulting in a cardiac arrest. But the doctors at that hospital just noted ”drug ineffective” in my journal and never considered that the drug itself had induced my arrhythmias.

Torsade de Pointes – this is not how you want your ECG to look like. https://jetem.org/torsades_depointes/

As this point, I was taken off the Flecainide and my body flushed the drug out. I was myself again. Although the drug didn’t do what we hoped for, my adverse reaction to it became an important clue. Several new syndromes were considered, the geneticists dug deeper looking for genes which could be related with abnormal ion channel function. But nothing was found.

As things looked bleak, a new medicine was brought up for consideration – Verapamil. This one targets the Ca++ channels instead of the Na+ channels in the heart. The theory was that since my body has a hard time regulating calcium due to the FHH, maybe this ion channel needs some moderation. But it was a long shot and my doctor at the ward told me I shouldn’t hold my breath.

After just a day on the new drug, I felt great! And this is where things finally started to look better. After being discharged for a month, I came back for a cardiac stress test where you pedal on a bike while being monitored to evaluate heart function during work load. And the results just came in! All vital parameters have improved! 🎉 Before, I got palpitations every time i exerted myself, especially in the mornings. Every morning was just about surviving until lunch. And all of those have disappeared! Going from thousands of PVCs per day to 20-30.

Along with that, my crippling anxiety disappeared too. It feels like I’m finally clear-headed after living the past year in a fog and honestly like I’ve gotten my old self back. There are still many follow-ups left before I know for sure that I’m protected from more serious arrhythmias and I’ll probably live with cardiac issues for the rest of my life but getting some good news for the first time in a year warrants at least a modest amount of celebration :)

Shout out to all the staff at Karolinska University Hospital who’ve worked relentlessly taking care of me and trying to cure me. Hopefully, I won’t have to be a regular at the ward anymore.

And lastly to the love of my life Malin who’ve endured with me during all this time and given me support in the darkest of times ❤️

McDonald’s break during a transport between cities. An hour after this picture was taken I had another cardiac arrest inside the ambulance.